Introduction by Bill Larson, Pala International

This is Burma, and it will be quite

unlike any land you know about…

— Rudyard Kipling, Letters from the East

One of the most interesting things about the Internet is hearing from old friends. This occurred for me in January 2011 when I got a note from Herb Ehrmann, introducing himself as one of Martin Ehrmann’s sons and saying that he’d like to be in touch. I knew Martin for several years in the late 1960s until he passed away in 1972. He visited our Stewart and Tourmaline Queen Mines and enjoyed our legendary mine parties. Martin Ehrmann is perhaps the preeminent mineral and gemstone dealer of the 20th century. As his biographical profile at The Mineralogical Record states,

Ehrmann became one of the first mineral dealers to literally travel the world in search of fine specimens. He was already visiting Tsumeb in the 1950s, made his first trip to Burma in 1955, was a regular visitor to Brazil where he acquired fabulous things, and had contacts for tanzanite crystals in the 1960s. He had stories to tell about acquiring specimens in Ceylon, Mexico, Russia, Bolivia, Colombia and Australia.

After a wonderful, reminiscing phone call I invited Herb and his wife Connie to visit Pala International and the upcoming Tucson show. They came to Tucson, loved the show, and we had a great time together, planning a follow-up visit in Fallbrook. They came to our office two weeks ago, bringing along a copy of an unpublished Mogok manuscript, written by Martin, and a box of slides. Martin visited Burma seven times beginning in 1955, until 1962 when Ne Win banished Westerners from Burma. What I found amazing upon reading his story is that his adventures are still so similar to my own in Burma (33 trips between 1993 and 2011). Certainly many things are very different, not the least being the ability of Martin to purchase a 20-carat pigeon’s blood ruby in Mogok, which these days would probably only be be found in Geneva. And Martin was able to conduct business inside the country; since 2002 we are not allowed but must buy in Thailand, although we can communicate what our needs are—by email! Ruby and jadeite are banned from the USA, so all this is sold elsewhere (see the latest auction results here).

So with realization that this is not a final version, being unfinished by the author, we have permission to present this wonderful window into Burmese gemstones some 50 years past.

There are six chapters in all; Pala is honored to bring them to our readers in monthly installments, and we encourage your feedback.

See also Chapter Two, Chapter Three, Chapter Four, Chapter Five Part One, Chapter Five Part Two, and Chapter Six.

Chapter One

|

| Martin Ehrmann, in a pre-1956 portrait by Bushnell Photo Studio, Los Angeles. (See this note.) |

After twenty years of buying and selling gemstones and mineral specimens, in a small way, I finally thought that my apprenticeship had ended. I believed that now I had sufficient experience and knowledge to fulfill my great desire and ambition to visit Mogok. Mogok is known to the Burmese as “The Ruby Mines,” and is called “The Valley of the Rubies.” It lies north in the Union of Burma about five hundred miles from Rangoon. It is situated between high jungle-covered hills. Mogok originally was called Thahapainpin, “Pomegranate,” for the fruit growing abundantly in these hills. The finest rubies and sapphires are found there. Now that I had decided to take the plunge, go to Burma and buy the gems and minerals directly, I would avoid the middlemen that I had been dealing with, some in the United states and others in the European market. London and Paris were the best markets for Burmese rubies and sapphires. My purchases weren’t always profitable. I learned by experience to minimize non-profitable purchases in order to avoid great losses. Each experience added to my knowledge of quality, desirability and the value of gemstones.

I started my business in 1930 during the depression. It was not an easy task. Nevertheless, I managed well. I was a small operator and eliminated overhead expenses by using my home as my business office, and my wife served as my secretary, working whenever our two small sons would allow.

I began to attend meetings at the New York Mineralogical Club and met some of the oldtime members such as Gilman S. Stanton, James G. Manchester, George English and Ernest Weidhaas. I also met Dr. George F. Kunz of Tiffany’s who was the founder of the New York Mineralogical Club.

I was a struggling, hard-working young man who passionately enjoyed his newly acquired profession. I began to sell gemstones to the museums in New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, and to many museums and universities in the East. I later traveled to the Midwest visiting museums and universities there. I was able to sell fine mineral specimens and gemstones to these museums. Although restricted in their budgets during the Depression, they still had some money. When, at the end of the week, I had earned between $25 to $30, I felt very lucky. Slowly and systematically my list of regular customers increased.

|

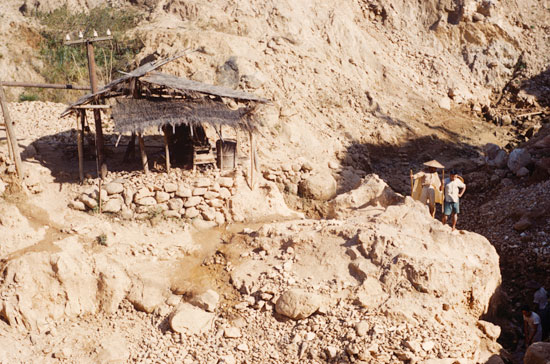

| An American Army jeep, now owned by Ehrmann’s guide U Khin Maung, which “became a good friend” as the two traveled in it for seven or eight yearly visits to Burma. |

My first trip to Burma in 1955 took a considerable amount of planning. First I had to line up the people who were interested enough to finance my trip. I had two wealthy wholesale dealers in mind from whom I had purchased many gems in the past years and who had sufficient confidence in my ability to become a gem buyer for them. Both men were agreeable and eager to support me in this venture.

Two days after obtaining their backing, I was on an airplane to Rangoon. The plane made a stopover in Bombay and one of my new associates wanted me to visit an important gem dealer there who had informed him about a private treasure of fabulous jewels belonging to a wealthy maharaja for whom he was the agent. As I was already recognized as a jade expert, my associate asked me to examine and evaluate several pieces of jade jewels of the finest quality. There were two jade cabochons of unusual size, and a jade bead choker consisting of 28 beads, 14 millimeters in diameter, of the finest emerald color and translucency imaginable, and very evenly matched. The two cabochon jades were of the same quality.

Returning to my hotel, I put in a call to my associate in New York.

“Eddie, this is Martin in Bombay. The jades, both the cabs and beads are sensational; the finest I have ever seen.”

“Are they emerald green and translucent? Have they any, spots?” Eddie asked.

“The two cabs are perfect shapes, weigh about 35 carats each and are the finest in existence. The choker is much better quality than the jade necklace bought by you know who.”

“What about the price?” Eddie inquired.

“It is high, but considering the rarity and quality, my advice is to buy them.”

We discussed the price at great length and I received instructions to pay so much and no more.

Two days later I sent a cable giving him the final price.

The next day a cable arrived: “If that’s the best you can do, buy.” A few days later the jades were on the way to New York.

I had read everything available about Burma, but I didn’t learn very much. The anticipation of excitement and adventure in an exotic unknown land was increasing. These thoughts occupied my mind as we were flying from Bombay with a stopover in Calcutta to Rangoon. After leaving Calcutta, we were flying over the Burma forests. I saw nothing below us [but] jungle and overgrown mountain scenery. As I looked out of my window I saw a snakelike body of water. From the air route maps I had studied, I knew it was the Irrawaddy River. Rangoon was located at the delta and soon came into sight.

Rangoon is an exotically impressive city with wide well-laid-out streets and many beautiful parks within the city limits. It is not the cleanest city in the world. The ravages of World War II were still visible in the many bombed-out buildings with all their rubble. Some slum sections, perhaps not as bad as in India, came into sight on our way to the city. Crowds and filth were evident everywhere the taxi took us. The new residential section of the city was well-kept with many beautiful mansions standing majestically on Prome Road, the finest residential street in the city. We passed many temples and pagodas of beautiful architecture, though not as elaborate as those in Siam. The Sula Pagoda in the center of the city has a tower of over 50 feet high covered with 24 carat gold leaf to which gold is added regularly every few years. This leaf is donated by the people of the city. The tower is reputed to be worth many millions of dollars. We also passed the outskirts of the Shwedagon Pagoda which is located in the residential area on a lovely landscape two miles square. This pagoda, with its golden spire, is the largest and finest Buddhist temple in the world. Its tower, too, is worth millions of dollars.

I checked in at the Strand Hotel and was given a lovely room with good bathing facilities. In the center of the room stood a table. On it was a large bowl of fruit and a welcome card from the manager. After unpacking, bathing and changing, I went down to look over the hotel. The lobby was very elaborate and roomy and there I found a small gem shop. I walked in and met the first Burmese gem dealer with whom I later had many transactions. His name was Aung Chi. He showed me many rare stones, quite a surprise to me as I didn’t realize that such varieties of semi-precious stones were found in Burma. I purchased a number of the smaller rare stones at a fairly reasonable price and by the end of our first meeting, we had become good friends. He told me that he didn’t have anything of great value at the moment but gave me a number of addresses in the city of Rangoon. When I told him I was a wholesaler and interested in large quantities of gemstones and mineral specimens, and that I did not think I could do as well in Rangoon as I could directly at the mines in Mogok, he suggested a young man from Mogok who might become my agent. He told me that his parents lived there now and that he did not have very much knowledge of gemstones but he had a good knowledge of the English language as he had worked for the British and American armies during the occupation of Japan. I told him I was very much interested in meeting this young man and he said he would arrange it for the next day.

|

| A real character smoking a cheroot, a traditional Burma cigar. |

According to my normal operating procedure when visiting a new country, I called upon the American Embassy the following morning. I met the first secretary of the Embassy, Mr. William Ballard. He seemed very enthusiastic and fascinated with my plans to visit Mogok but warned me that Mogok was in a rebel zone and that communications were sometimes completely severed. Highway robbers—“dacoits”—attacked and kidnapped travelers and held them for ransom. Therefore, as an official of the American Embassy, he advised me against this trip. But personally, he said that he wished he could go with me to share the adventure. We had lunch in his home not far from the Embassy. The interior decoration of his home was magnificent. Curios from many parts of the East where he had been stationed were tastefully displayed in various parts of the house.

My host told me many exciting stories and one particularly interesting. It was about a Lama Priest he had met in Nepal in a Buddhist Temple outside the city of Katmandu.

“I apprenticed my priesthood in Lhasa, capital of Tibet, in a monastery where the Dalai Lama had his private quarters. We had no restrictions on our movements within the monastery and could meditate in our free time wherever we pleased. One day, in 1952, a year before the Communists annexed Tibet to China, I came upon a small room which was very unlike all others in the monastery, as it had an iron door which was unlocked. My first impression was that it was a prison of some sort but on closer inspection I discovered that it was a treasure chest filled with stones of all colors of the rainbow and in sizes from one inch to fist size. There were sapphires, rubies, diamonds and pearls piled on top of each other, all in an iron chest that stood on a table against the wall of the room. I looked at this splendor without the knowledge of what they really were and what value they possessed. I later confessed to one of the senior Lamas about my discovery. I was then told that this collection, worth many millions of dollars; was donated by wealthy Buddhists from India, Burma, and Ceylon as gifts to the ruling Dalai Lama for more than a hundred years and that they were always stored in that very room which was never locked and could be seen by anyone in the Monastery.” That was the end of his story. But, he added, when he left being assigned to a Lama Temple in Katmandu, he had heard that all the jewels were removed by the entourage that left with the Dalai Lama when they fled from the Communists a few years later.

The next morning in the dining room of the Strand Hotel where I was having breakfast, the waiters were all Indian sheiks, pleasant and helpful. During the course of my meal, a young man, short and squatty, with a round smiling face, almost moonlike in appearance, came to my table and asked, “Are you Mr. Ehrmann?” And I said, “Yes.” He said, “May I sit down? I am U Khin Maung. Mr. Aung Chi sent me here to talk to you about a possible trip to Burma with you.” He told me immediately knew very little about gemstones but that he was born and raised in Mogok and that his parents still lived there and knew most of the miners and most of the mine owners, and that he could be very helpful to me. He was friendly, had a good personality and I liked him immediately. After more conversation, I decided to hire him as my agent.

After breakfast U Khin Maung invited me to take a sightseeing trip through Rangoon. He owned a jeep which he had purchased from the American army before it left and it was in good condition. He told me that normally this jeep was in Mogok but he had to move some things from there to Rangoon and that was the best way to do it, but it was being driven back to Mogok by his younger brother who had driven down with him. This jeep became a good friend as we traveled in it a good deal during the next seven or eight years on my yearly visits to Mogok. He was a wonderful guide and showed me the good and the bad of Rangoon.

After about two hours U Khin Maung took me to his home and introduced me to his wife. I thought she was his mother as the lady was at least twice his age. It was his wife! Apparently after his army career was over he was not in good financial condition. He met this lovely woman twice his age who was in the silk business selling longyis, sarong-like affairs worn by the Burmese men and women.

Her office was in their home. The living quarters were in the back and the business quarters in the front. It was quite apparent that he married her for convenience and, surprisingly, it was a very successful marriage. He spoke of the many habits and superstitions of the Burmese, and he was always very enjoyable to hear.

During the next few days U Khin Maung and I visited many dealers in Rangoon and looked over their stocks. I made no attempt to make any purchases, even though I did see many nice stones which I would have liked to own. I mainly wanted to get acquainted with the prices and wanted to make sure what Mogok’s, prices were going to be before making any commitments. I did buy one stone that I couldn’t resist. It was an emerald-cut sapphire weighing 25 carats, cornflower blue, flawless, with a very good shape. The price was right. That was actually the only purchase I made while on my first trip to Rangoon.

I decided to leave on the following Friday by air from Rangoon to Momeik which is the airport nearest to Mogok. This plane flies only once a week, and always on Friday.

Transportation within Burma is poor. There is a railroad from Rangoon to the north. It is old, dilapidated and very slow. A trip to Mandalay, a distance of 450 miles, takes about four days and it is extremely dangerous. Each train leaving Rangoon is preceded by an armored car with a company of soldiers, as these trains were frequently attacked by marauding bands, insurgents roaming the jungles of Burma. Even this protection did not prevent frequent attacks and much loss of life. Another mode of transportation was by slow, crowded and uncomfortable river boats on the Irrawaddy River, the most important river in Burma and navigable for almost 1000 miles. Such trip is a combination of four days train travel to Mandalay, two days by boat to Thabeikian and 60 miles by jeep to Mogok. Air travel is the finest mode of transportation in Burma. But I promised myself that on subsequent trips I would try both the railroad and the boat just for the sake of adventure.

The Union of Burma Airlines is most efficient, flying regularly to all points north. The planes used are either Dakotas or DC-3s, all flown by Burmese pilots trained in England. These two motor planes are found best for the short distance flown. There were two daily flights to Mandalay and flights once a week to the capitals of all states, thus making air travel the only efficient way to get anywhere fast in Burma.

|

| A women’s market in Mogok. The woman at lower left appears to smoke a cheroot of her own. |

The plane we took on Friday at 8:00 a.m. arrived in Momeik about noon with a stopover in Mandalay for about an hour. The town of Momeik was conspicuous to the newcomer by the sameness of the houses, raised on piles to protect them from floods during the rainy season. When the plane pulled up to a ramshackle bamboo hut, we immediately got off. U Khin Maung asked me if I noticed the soldiers around the plane. I nodded. He said they are there because the authorities expect a raid every time a plane lands.

We were met by U Khin Maung’s jeep for the 28 miles drive to Mogok. This brief trip is usually accompanied by an element of danger since the roads are frequently mined by the insurgents who roam the jungles. Cars are frequently attacked by dacoits and sometimes blown up. The insurgents are of a different breed. They are political enemies of the State, either white communists, red communists or green communists, and sometimes plain criminals who had come north from the big cities to hide in the jungles and to earn their living with the insurgents. I am talking about the days of the government of U Nu, not of the present military government that is in power now. As it is practically impossible to get permission to go anywhere inland, it is very hard to say what conditions are now. But from what I understand, the insurgents in the northern part of the States are still very active.

The drive from Momeik to Mogok was accomplished without any incidents. This route brings us from 800 feet level to 4000 at our destination. The climb is continued through extraordinary interesting country with its hair pin curves and fragile wooden very unsafe bridges over the ravines. Occasionally green valleys appear through thick jungles. Then, suddenly, terrible isolation, and ruined pagodas come into view. Here and there is a village around which are picturesque rice paddies. The roads are deteriorated and appear to have had no care in years. It is an ideal area for an ambush.

Soon we saw a lake; behind the lake we saw houses also built on stilts which looked very much alike. We had arrived in Mogok.

|

| Pigeon’s blood ruby on calcite from Mogok. The ruby crystal is about the size of a man’s thumb. The specimen currently is on display in the San Diego County Natural History Museum’s exhibition All That Glitters: The Splendor and Science of Gems and Minerals, through April 8, 2012. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

Mogok is situated in a magnificent valley surrounded by majestic mountains which are studded with temples and pagodas, some very modern and others thousands of years old. Geographically Mogok is considered part of the Burma State although it is actually located in the western part of the Shan State. This dates back a long time before the English occupation of Burma. It was a kingdom then and all of Burma was ruled by Burmese kings. Because of the vast wealth in the Mogok area, these kings retained their rule by fighting the Sabwas (which are the same as maharajas of India) who tried to wrest it from them. Even under British rule, the Mogok area was kept a separate entity as an independent state. A British commissioner was appointed for this area alone until Burma became a republic uniting all six states. Only the state of Burma was actually the Kingdom of Burma. The other five states are ruled by individual Sabwas. These Sabwas are still very powerful politically, are holding ministerial rank; as Sabwa of his own State, he is the minister representing his State in the Union Government; in addition, he may, and usually does, hold another political office. Of course, under the military rule of Ne Win, this has all changed in present-day Burma.

The Mogok Valley is about 20 miles long and 2 miles wide. In the center of the village of Mogok is located a beautiful lake created by digging of precious stones during the ruby syndicate era. The Mogok gem area reaches to the city of Momeik, a distance of 20 miles to the north and 60 miles to the west up to the village of Twingwe and Thabeikian on the Irrawaddy River. Mogok has a moderate climate. During the winter the maximum temperature is 25 degrees during the night and early morning. During the day it rises to 70 degrees. In summer the evenings are not very cold and the maximum day temperature is about 95 degrees. It has a very heavy rainfall ranging from 90 inches of rain to 175 inches in the rainy or monsoon season from May to November.

The only industry in the entire area of Mogok is the mining of gemstones. There is hardly any cultivation in this area. Consequently, even rice, which is the staple food, has to be brought in from Momeik.

In addition to the temples and pagodas one sees in the mountains, various plants of gorgeous colors, brightly colored, blooming magnolia trees and cherry blossoms are also seen. One shrub, similar to the rhododendron, grows allover the mountains. The natives are superstitious about these shrubs, believing that they are created by the good spirits hovering in the area and called the gods of the mountains. Wildlife is also abundant. Many varieties of birds can be seen almost any time of the day. Elephants, tigers and various species of the deer family thrive in the mountains and nearby jungles.

U Khin Maung, my agent and interpreter, made arrangements for us to stay with his family at their home where his father, mother, two brothers and a girl, a sister, lived. He told me the sister’s Burmese name but it was too difficult for me to pronounce and I named her Princess which she seemed to like very much. She proved to be very helpful to me by taking care of all my chores, like taking my clothes for cleaning, laundry, and getting my shoe shines.

The house was a typical Mogok hut, built on stilts on the ground on a concrete slab and one wall is also concrete. The rest of the walls are all woven bamboo held together by teakwood beams. The roof was of corrugated tin. You have to go up one flight of steps to reach the living room. Beyond the living room there is sort of a corridor with all sorts of cubbyholes which serve as sleeping quarters, storage rooms, et cetera. I was given a cot in the corner of the living room. In all homes in Mogok the living rooms serve a dual purpose, since they are also the family shrine. In one corner a pagoda occupies the most prominent place in the room. In front of it is a table on which are placed flowers and bowls of rice, changed daily as offerings to 8uddha. Daily prayers in a prone position are said to Buddha morning and night. According to the Buddhist religion no one can ever enter a pagoda wearing shoes, so everyone takes off his shoes before entering the living room of any house in Burma.

There are absolutely no sanitary facilities. In the back of the house, behind a bamboo wall, there is a little trench which was used as a toilet. The water supply comes from pumps. Some houses have their own pumps in the back but in front of each two or three houses there was a public pump. I noticed many times that people early in the morning took baths under these pumps. As I mentioned before, the people there wear longyis.

|

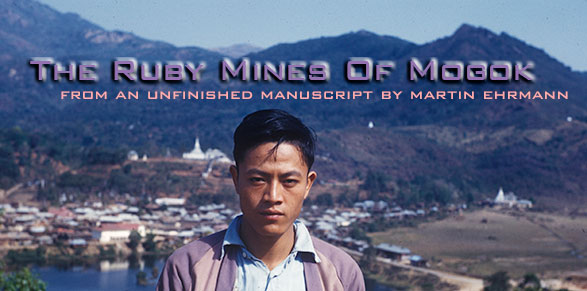

| A friend of Martin Ehrmann’s stands with Mogok, and Lake Mogok, in the background. |

The men come out in a longyi tied to their waist. The women come out in a longyi tied over their breasts. They carry a towel and a dry longyi with them. There was a line where they were hung. And while they were washing themselves under the hand operated pumps, I watched very carefully but they were so skillful at it that at no time was anything more visible than when they started. After they finished, they changed from one longyi to the other. This was also so skillfully done, that no parts of the body were ever exposed enough to see. After a few days of this I tried it myself and decided I needed a bath and I thought, well, if they could do it, I could do it too. So one morning, after the prayers were done, it was very cold and I was waiting for the sun to come out and warm up a little, I just went under one of the pumps, took my extra longyi and a couple of towels and started bathing myself. Everything went well at the beginning and I was able to soap myself and then rinse off. But at one point my longyi slipped a little and suddenly I heard all kinds of laughter from all the neighboring houses so apparently I was being watched taking a bath too. But after the first trip the first time, it became sort of a natural thing and I never heard that laughter again.

On our first evening in Mogok we retired early after a typical Burmese meal. We ate a tasteless thin soup containing mustard-like greens, followed by a white rice and curry sauce with bits of pork and other tasteless but spicy vegetables and tea to follow.

About 6:00 a.m. I awakened by the morning prayers of all our neighbors. We had our breakfast of two boiled eggs, bread and butter and coffee. I had brought canned butter and instant coffee with me.

We started our tour of the town with a courtesy call to the S.D.O., subdivisional officer, who acted as mayor, chief of police, fire chief and magistrate, as well as chief mining inspector. His name was U Lha Tint, a charming and personable young man of about 30. He is respected by all the 20,000 inhabitants of the area. He gave us a most cordial welcome and promised to give us advice and help in any way we wished. After the customary cup of coffee followed by a cup of tea, we departed, assured that we all had the cooperation we needed from the law in Mogok.

U Khin Maung and I then started out on our first tour of visiting the mine owners and dealers in Mogok.

After the end of this first day, my experiences and feelings were mixed. Amazing, exasperating, frustrating, instructive and illuminating.

We had started out early in the morning to begin our transactions. Our first stop was the home of the most important dealer in Mogok. After two hours of imbibing the customary cups of coffee and tea along with much conversation, I became impatient and asked my agent about seeing stones. Studying my face intensely the dealer finally exhibited one paper containing a very poor star sapphire. Although I wasn’t at all interested in it, I wanted to be polite and inquired about the price. If I recall correctly, I had already judged $25 to be a fair price for the stone. When my agent informed me that it was the equivalent of $500 he was asking, I almost exploded, but casually tossed the stone back to the dealer. I asked to see more stones but was told most politely but firmly that there were no others.

We had similar experiences with five other dealers that we visited that day. At each of our calls, one stone would be shown at tremendously exaggerated prices that were completely out of line. Even though I knew that the prices were inflated for bargaining, I thought it would be ridiculous and insulting to make offers amounting to perhaps five to ten percent of the asking price. That evening I went over the day’s experiences and discussed them with my agent. I must emphasize that great reverence and respect are accorded to age by all Burmese. Because my agent was a much younger man than I, that instinctive respect for my age prevented him from giving me an immediate analysis of my day’s errors. After long questioning and discussions, I finally did gather that it was considered bad form not to make an offer on merchandise for sale, no matter how low. That is, if you looked at it and liked it. If not, you just returned it and asked to see something else, saying that you were not interested in this particular item. I asked whether my offer of $2 for a stone quoted $100 would not be considered insulting. He assured me my offer would be graciously received as a compliment to the gemstone. But the eventual selling price would depend upon the buyer’s patience in his bargaining abilities. Time is of no importance in Burma, and long patient bargaining is an essential part of trading there. My agent further explained that the high asking price was an attempt by the dealer to learn the purchaser’s idea of the stone’s worth. Apparently their idea is that the buyer knows the value of a stone and knows how much he is going to pay for it.

It took me a while to assimilate this information and I tried to act accordingly since it was so different from our way of conducting business and of the ways I was used to in other countries. However, I knew that I must follow my agent’s advice in order to make any progress at all.

|

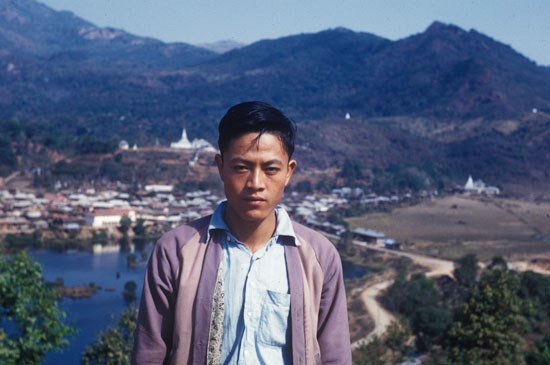

| An all-electric mining hut in Mogok. |

The next morning we followed the same procedure. We entered the house, took off our shoes, and sat on a mat on the floor awaiting the miner or dealer to come out and greet us. After the usual long drawn out preliminaries of coffee, tea and much conversation, I was at last shown a fine gem sapphire weighing 6 carats for the asking price of $1,500. After careful examination I decided I could pay about $500 for it and I asked my agent to offer $300, giving myself enough leeway for the expected bargaining. Although I couldn’t understand the ensuing conversation, I saw the dealer smile and express appreciation for the offer. He said, “Quaray,” a word which I was to hear very often and which means “We are too far apart.” I instructed my agent to tell him that he was asking much too much for the stone than it was worth and that I would raise my offer if he would come down. The next price asked was $1,000, already a one-third reduction. I had my first feeling that gem buying in Mogok might eventually prove successful. I raised my first offer by $100 and he went down another $100, whereupon my agent suggested that we let the dealer think it over and we would return the next day.

The following morning I requested the lowest price and was told that the very lowest would be $700, take it or leave it. My final offer was $500 which was graciously accepted, leaving me in a much more cheerful frame of mind about the entire situation. With my newly acquired education I was able to make a few purchases while on my first trip in Mogok.

I did find out that the average mine owner or dealer was very reluctant in showing the fine stones to a newcomer. He wanted to make sure first what kind of buyer he was, if he knew his stones and if he was financially sound. In the process, I slowly became aware of an important factor in the economic life of the miners and dealers, and generally the people of Mogok. The living conditions of most are very much alike, whether rich or poor - very primitive, requiring only a very small sum of money for their daily needs. Even the most prosperous families spend probably no more than $I,OOO a year for all living expenses. As a result their wealth is measured in terms of the quantity of their stock of gems. Usually they will only sell enough material to take care of their immediate needs.

I found out a good time to buy expensive gemstones is when one of the wealthier dealers decides to build a pagoda which they do very often. Some of these pagodas cost as much as $100,000 and they include all the imported sanitary equipment that money can buy. In addition to that, with the pagoda go one or two priests that become this miner’s life responsibility. In later years the mode of living in Mogok changed considerably. Many of the wealthy dealers built magnificent homes with all wonderful sanitary facilities, bathrooms and all sanitary conditions found in the finest homes anywhere.

The brokers had suddenly become aware of my existence. Sometimes they came in droves without announcing themselves. They stood in line awaiting their turn on the steps leading to my quarters. They were entirely unhurriedly at ease as though they had their whole lives before them and nothing else to do.

U Khin Maung brought the first broker in line to our living room. He carried a large heavy sackcloth which he emptied in front of me. I gazed bewildered at the pile of peridots in front of me, the first important lot of this gem stone that was shown me in Mogok. I estimated the lot to weigh at least seventy-five pounds. While I was occupied examining and assorting this lot, I noticed U Khin Maung doing the same thing forming another pile next to mine. He looked pleased and totally at ease during the whole examination of this lot. There were many fine crystallized specimens of sizes I never believed existed. They had very sharp faces but were etched in forms of very tiny triangles throughout the whole crystals. I could just visualize the faces of our museum curators who had never dreamed that peridot crystals of this size existed.

Not all were crystals. Many were broken fragments but in large sizes, and clean and cutable. I estimated that I could cut stones weighing from ten to about three hundred carats from this lot. The lot also contained many useless flawed pieces without any value. I wanted to buy this lot. The moment had come to start negotiations with the broker. During our examination I occasionally looked at the broker who not for one second took his eyes off the lot. He had a nervous twitch which he tried to shake, but couldn’t. I finally gave the sign to U Khin Maung that I wanted to buy the entire lot. When negotiations started, I noticed that all anxiety had left the broker and that he was completely at ease again.

Soon I found that he only wanted to sell about a third of the lot on instructions from the miner [at] Pyaung Gaung. [Pyaung] Gaung [Sein] is the name of peridots in Burmese [literally “green stone from Pyaung Gaung” —Ed.]. [Sein] means [green] stone. It is located, unfortunately, in an insurgent area, only ten miles from Mogok, but no one in Mogok ever dared enter this area. The agent’s persuasion was of no avail. The owner didn’t need the money and wouldn’t sell all until he needed more money which he wouldn’t need until after the Burmese New Year three months hence. He told us that the owner was quite positive that the price would not go down since all the miners and dealers were learning that prices continue rising which also made for reluctance in selling. They all believed that it is better part of wisdom to hold their gems until they needed the money. I just sat there watching the broker in disbelief. I finally made up my mind to enter the insurgent territory and negotiate with the owner for the entire lot. U Khin Maung was against it and so were the other dealers whom we consulted. I finally went to see the S.D.O., the Subdivisional Officer, and asked his advice. He too was against such daring venture. The only one who didn’t think it would be dangerous for me to go to Pyaung Gaung was the broker who was a native of Mogok and practically guaranteed my safety. The only drawback was the language barrier as no one in the village spoke English. But I felt that I could negotiate by sign language and write figures on paper.

Reluctantly it was finally agreed that I leave by our jeep with the broker early next morning, not taking anything of value with me. If negotiation was successful, the broker would return with me and the peridots to Mogok, and he would be paid there.

|

| A village on the way to Mogok. These towns would look the same if visited today. |

We started off the following morning, as agreed, and after almost an hour we were about two miles from Pyaung Gaung. The broker asked me to stop there and wait in the jeep until he returned as he wanted to talk to the chief of the insurgents and tell him the reason for my visit. If he didn’t agree, he would come back and we would just return to Mogok. If he did, he would bring horses so that we could ride in the two miles to the village and that I would be able to negotiate with the owner.

An hour later a horse and buggy arrived with the broker and the chief of the insurgents. He was with the broker to either approve or disapprove my entering the village. He was a short man even by Burmese standards, about 50 years old, paunchy but very compact. He had black hair, very shiny from the hair tonic he had applied to part his hair in the middle. To my surprise he addressed me in poor but understandable English. He had a pleasant high pitched voice and a nice, easy manner. “Are you English?” were his first words. When I replied that I was an American, he smiled and seemed pleased. We talked about many things, including politics. He finally asked me if I was afraid of insurgents. I told him he was the first one I had ever met and added if all insurgents were like him, there would be no need of fear. He then entered the jeep without saying anything further and he drove on to the village which we reached in ten minutes.

It was a settlement consisting of about 30 houses, some were thatched, others had corrugated tin roofs, all built on stilts. There was one big building in the village. This was where the chief of the insurgents lived and all activities were apparently directed from this building. I was dropped off at one of the houses. The chief bade me an abrupt goodbye and wished me good luck, and left me standing in front of this house. Not knowing what to do, I waited at least ten minutes when finally the broker showed up with his horse and buggy and we climbed the stairs together. It was the owner of the peridots that greeted us when we took our shoes off before entering the living room. He welcomed me with dignity and politeness, all in Burmese which I didn’t understand.

Again the sack of peridots was dumped on the floor and the owner, without assorting, divided one-third and said this is what he was going to sell today. The balance he wouldn’t sell until he was in need of the money. In sign language I made him understand that I wished to buy the whole lot and would give him a very good price to make sure that even if he sold them at a later date he wouldn’t take any losses. Again he indicated that he didn’t need the money and therefore would only sell this third and how much would I bid for it. I said that I never made bids, that he would have to give me a price and if I were satisfied, I would buy it. He wrote a price which seemed rather reasonable but knowing the Burmese, I knew I couldn’t just accept. I wrote the price of the lot and made it about a third of what he indicated. Smilingly he said, “Quaray,” the usual “We are far apart.” I indicated I would buy it all for double the price that I had indicated. At first it seemed to interest him but a few minutes later he again pointed to the third he had separated and wrote down a new figure. I raised my figure a little bit and finally we came to an agreement on this lot. But I wasn’t ready yet to let the balance go. In sign language I tried to explain to him that if I buy the lot I would give him so much which was much more than he actually expected, but that he didn’t have to take the money right away. I could give the money to anyone he trusted in Mogok and he could draw from him as he liked, either in one month, two months or even wait until the Burmese New Year. He couldn’t resist the temptation of this offer and he finally told me that I could buy the lot, the broker would take it with me, I could pay him and he would arrange payments to him as needed. I could not have felt more elated if I had bought a million dollars worth of fine gems when I bought this lot of peridots which in value was nothing like any of the more precious stones like rubies or sapphires. It was a mere pittance but the fact that I was able to buy such an unusual fine lot of such an unusual fine gem pleased me immensely. After much more conversation but with complete dignity and politeness I left. The broker took the lot with him and put it in the jeep and asked me if he could drive me back to Mogok.

Arriving there an hour later, it was exactly 3 o’clock in the afternoon. We were gone exactly nine hours. By the triumphant expression, U Khin Maung immediately knew that I had been successful. But he also showed his elation that I was back safe and sound. I felt that I had made a very successful trip this time in Mogok and U Khin Maung had made a good bit of money and to his commissions that he earned I added a nice fat bonus which pleased him very much.

The next day we returned to Rangoon and I stayed a few more days visiting some more dealers. I purchased quite a number of small but salable star sapphires and faceted sapphires and caliber rubies which were specially ordered. These are skillful goldsmiths in Mogok who work only in 22 carat gold. When I saw the bangle bracelets they were making I bought quite a number of them. They were set both with rubies and sapphires. Even though the quality of the stones was not very good, they were nevertheless attractive and I thought they would be very good sellers. As it turned out, I was right.